Internationally, Dutch architecture firms and projects played important roles in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. With the notable influence on architecture and urbanism in recent history by figures such as Hendrik Petrus Berlage, Gerrit Rietveld, J.J.P. Oud, Willem Dudok, Aldo van Eyck, Piet Blom, Herman Hertzberger and Rem Koolhaas, there seems to have been something about Dutch architecture culture that caused architecture and architects to thrive in the low countries. Major companies that originated in the Netherlands are currently at the forefront of contemporary architecture, contributing not only to the Dutch cityscapes, but making their mark all over the world. Most of these companies found the origins of their success in the 1980s and 1990s in the Dutch field. At this time in the Netherlands, young, starting architects where given chances and commissions by the national government for iconic, large-scale projects. This openminded role of the government was mimicked by the large and influential housing corporations in the country. This resulted in the apex of the much-debated open competitions, and the thriving of a new generation that brought innovation and a new view on the profession with it. The influence and progressiveness of key figures within the Dutch authorities, embodied in the functions of Rijksbouwmeester (Chief Government Architect) and Stadsbouwmeesters (City Architects), cleared the stage for firms like Mecanoo, MVRDV and Neutelings-Riedijk. It is through the possibilities that were given to these young architects that Dutch architecture became internationally regarded as innovative and optimistic, even christening the Dutch building process as a culturally inspiring phenomenon.1 The opportunities that were given to this generation by influential individuals such as Tjeerd Dijkstra, Kees Rijboutt and Riek Bakker caused Dutch architecture to become institutionalized as an export product in high international demand. The possibilities and the demand for innovation, the characteristics of the Dutch building culture in these decades, resulted in the creation of now famous architecture offices, with OMA and UNStudio as perhaps the most successful and financially thriving architecture enterprises of the past century.

It is these offices, once lauded as the promise of the future, that still seem to dominate the scene. There seems to be little left of the once so celebrated drive for innovation and the attitude of creating possibilities for upcoming architects attributed to the Dutch system. This discrepancy between the attitude of the final decades of the twentieth century and today in the Netherlands is a shift that has been noted by various practitioners, most notably Atelier Kempe-Thill. With its almost manifesto-like work Naar een Nieuwe Aanbestedingscultuur (Towards a New Tender Culture) from 2008, the two German-born architects try to indicate the shift of attitude and advocate for a change. In this document the two define the informality of Dutch culture as the roots for the prevailing attitude towards architecture in the 1980s and 1990s. An attitude that, according to them, has changed for the worse due to the introduction of the regulations imposed by the European Union. Though intended to bring the various European countries together and stimulate the cultures within the Union, the opposite seems to have happened in the Netherlands.

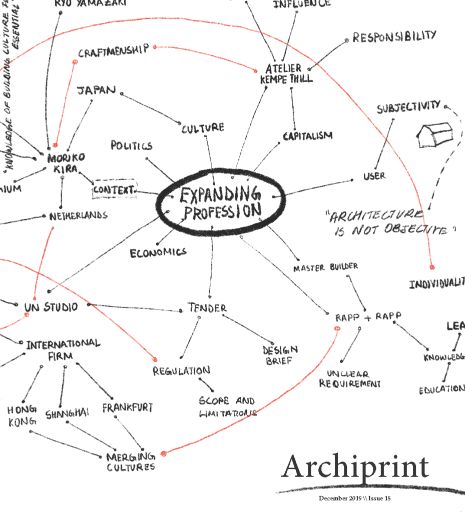

The observations of Kempe-Thill resulted in the question of whether or not the tender culture in the Netherlands is very different under these European rules when compared to other countries and whether or not a change of culture might be deemed necessary. Starting from the wish for change as proposed by Kempe-Thill, various practitioners, active not only in the Dutch field but also with experience in other countries, have been asked this question. Though we are well aware that the tender culture and the attitude towards this culture is one that has various constituents, it is the optics of the architect in regard to the tender culture that is dealt with in this issue. Through interviews with André Kempe (Kempe-Thill), Moriko Kira, Machteld Kors (UNStudio) and Birgit Rapp (Rapp+Rapp), this issue tries to examine the questions that arise from Kempe-Thill’s 2008 publication and the quest for change as advocated in that publication. In addition to this, the interviewed architects are asked to shine their light on the nature of the profession of the architect in relation to tender culture. In this issue, Dutch building culture is examined in regard to that in various European and non-European countries, such as Belgium, Japan and Germany. Within this examination, Archiprint 15 sets out to explore the differences in tenders and architecture across the globe through the experiences of these practitioners in an endeavor to answer the questions of what the current Dutch tender culture is, what might or might not be wrong with it, and what the role of the architect is within this system and how this might differ across the continent, while despite the fact that similar rules are applicable.

1 Kempe-Thill, Naar een Nieuwe Aanbestedingscultuur