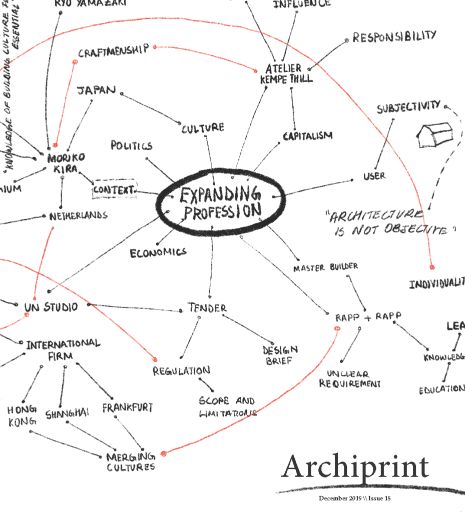

Whether you are an architecture student or an accomplished practitioner, chances are that over the years you have been battered with the same strong conviction that troubles the entire world of architecture: ‘The architectural profession is changing . . .’

It’s a rather dubious conviction. Of course it is not hard to see that the challenges that architecture faces today are vastly different from the ones it had to deal with a century ago. We have explored, invented and innovated, which has resulted in new challenges that allowed us to explore, invent and innovate some more. It’s a cycle, and it is as deeply embedded in the very nature of architecture as it is in any other professional discipline. So does this prove that our discipline is actually changing, or just that the architectural profession is a phenomenon of dynamic character – rather than static?

Having a profession means being professional in something. It suggests a societally acknowledged difference between amateurism and professionalism. In his essay ‘Why Professionalism is Still Relevant’, Melbourne University professor Dr. G. Beaton denotes the exact ingredients for this difference to exist:

‘A profession is a disciplined group of individuals who adhere to ethical standards and who hold themselves out as, and are accepted by the public as possessing special knowledge and skills in a widely recognised body of learning derived from research, education and training at a high level, and who are prepared to apply this knowledge and exercise these skills in the interest of others.’ 1

Beaton’s definition distinguishes three ingredients; access-, maintenance-, and execution of a profession. In the context of the architectural profession the first two are relatively obvious. First of all the conditional access to the architectural profession relies on knowledge and skills acquired through research, education and training. Secondly, Beaton’s suggestion of applying and exercising these skills as a way of maintaining the profession implies that the earlier explained cycle of exploration, invention and innovation is indeed inherent to the architectural discipline.

The third ingredient is, however, doubtful in the context of the architectural profession. As a way of executing a profession, Beaton implies the need for a set of ethical standards. Of course, no architect should make a building that could suddenly collapse, but there is more to architecture than just making buildings that last. It’s about the spatial organization of a society and as many architects think about this organization differently, they practice different sets of ethical standards. In architecture it could very well be that innovation relies on the existence of all these different ethical standards.

So how plausible is the conviction that the architectural profession is changing? This eighth issue of Archiprint is entitled ‘The Ideal Profession’. It does not aim to romanticize the architectural discipline by calling it ideal, but rather questions the balance between the way our profession changes due to our ideals, and the way our ideals change due to the profession. Its theoretical framework explicitly explores each of Beaton’s professional ingredients, varying between accessing, maintaining and executing the architectural profession.